This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

In Part 1 of this two-part Insight, we explore the origin of classified advertising in local newspapers and trace their evolution into today’s digital marketplaces. We also examine how network effects have driven the success of the classified advertising model, and discuss how early internet bulletin boards have developed into sophisticated digital platforms.

In Part 2 of this two-part Insight, we take a closer look at online recruitment platforms. We also highlight a Taiwanese case study, telling the story of how this recruitment platform has leveraged its brand strength, data access, and strategic investment to build a formidable human resources technology (‘HR-tech’) ecosystem.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

From Local Newspapers to Digital Powerhouses

Back in the dim and distant past – before the internet was invented – if you wanted to find a job, rent a house, buy a car or a second-hand refrigerator, then all you had to do was to turn to the classified ads section in the back pages of your local newspaper. There you could find everything from lawnmowers and babysitting work, to obscure collectibles and last-minute job postings.

The classified advertising section of a local paper was more than just a convenience for the community it served, it was also the lifeblood of the local newspaper business. Indeed, the classified ad model was so lucrative that Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger’s Berkshire Hathaway at one point owned as many as 30 local daily newspapers (and nearly 50 weekly papers), including The Buffalo News, The Washington Post, and Buffett’s own hometown paper, the Omaha World-Herald.1

These newspapers embraced an attractive business model: secure a near‐monopoly on local advertising, charge robust rates for classified ads, and lock in attractive, low-risk returns.

Rupert Murdoch famously described newspaper classified ads as “rivers of gold”. Classified advertising generated gushing streams of cash flow, which in turn nourished the floodplains of the broader media ecosystem.

The typical business model of a dominant local newspaper was extremely attractive. To reach their target audience, advertisers – the captive customer base – had little choice but to place their ads in the local paper. It was true that local papers had to invest in printing presses and delivery routes, which represented high fixed costs. But once a newspaper reached a critical mass in circulation, then the incremental margin on each new classified ad ballooned, providing a high and increasing return on capital.

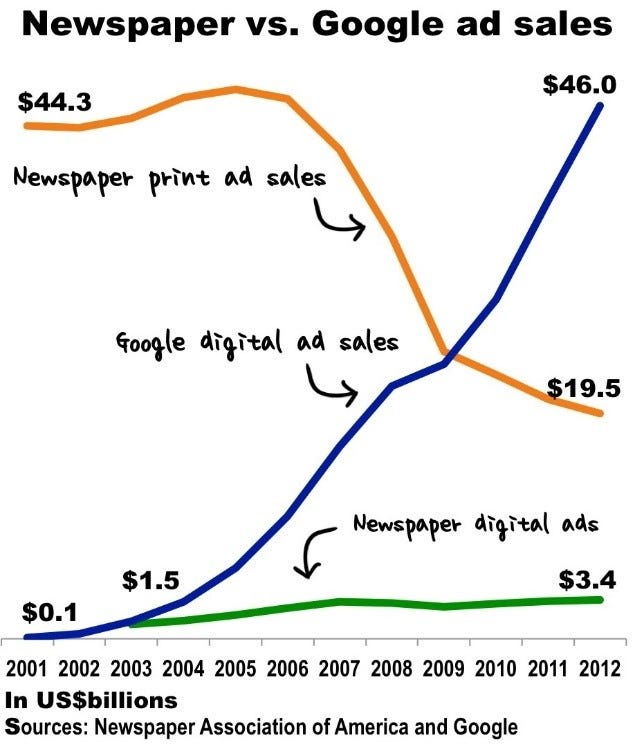

By the mid-2000s, however, the rivers of gold began to run dry (Figure 2.1). This was as advertisers increasingly realised the attraction of posting online where they could reach a broader audience, rather than in the back pages of their local rag. The Google Ads network (Figure 2.2), as well as digital classified advertising platforms such as Monster.com and Craigslist became particularly popular. The emergence of internet advertising eroded the core revenue stream of newspapers and upended their profitability.

Today, most classified advertising services have migrated online. Some remained tied to their newspaper roots or were spun out into separate entities,2 while other services sprung up in the form of newly-established internet ventures.3

No matter whether an online classified advertising platform specialises in a single vertical (e.g., real estate, automotive, second-hand goods, or jobs), or spreads horizontally across multiple domains, the business models of these internet platforms can be extremely powerful.

If an online platform in a particular vertical – for instance, recruiting or second-hand goods – is able to achieve ‘go‐to’ status in a particular geography, it can replicate many of the old ‘near‐monopoly’ dynamics of a local newspaper while avoiding its heavy printing and distribution costs. In Asia – home to large populations, rapid economic growth and deep internet penetration – these advantages are even more pronounced.

Classified Advertising & Network Effects

A ‘network effect’ arises when each new user of a platform increases the benefits for all other users of the platform. As the user base grows, the utility for each user expands – sometimes exponentially.

Two primary mechanisms drive this phenomenon: (1) direct network effects, where user-to-user connections foster engagement (e.g., social media platforms); and (2) indirect network effects, which are most visible in two-sided marketplaces where each new seller brings benefits for all buyers (and vice versa). Moreover, data network effects can amplify these dynamics: a growing user base generates rich datasets, which in turn help sharpen algorithms that boost user engagement and loyalty.

Prior to the internet era, local newspapers provided a good historic illustration of the power of network effects. Growing reader numbers drew in more advertisers, whose financial support funded better editorial content, which then attracted an even larger readership. In the modern digital era, ‘Metcalfe’s Law’ (Figure 3) codifies this pattern by suggesting that a network’s value scales roughly in line with the square of its users.

Today’s digital ecosystems – spanning social media, online marketplaces, classifieds, gaming, payments, and more – demonstrate how these effects can transform incremental user growth into a powerful, self-sustaining cycle.

A digital classifieds site, for instance, gains momentum each time a new buyer or seller joins the network. As postings on the platform increase and search algorithms improve, users can often pinpoint relevant offerings faster, thereby increasing the likelihood of more successful transactions.

By consolidating what might otherwise be scattered or opaque marketplaces, platforms also increase market transparency, drawing in more participants who value clarity and efficiency. Recruitment marketplaces demonstrate a similar ‘flywheel’ effect: an influx of employers attracts more jobseekers, which in turn lures further employers.

Early in their lives, however, many platforms face a ‘chicken-and-egg' dilemma: too few listings on a platform give little incentive for users to participate, while low user numbers deter new listers. Overcoming this hurdle often requires platforms to launch strategic incentives and/or subsidise user engagement until liquidity reaches a self-sustaining threshold. Once a platform does achieve critical mass and pulls ahead of the competition, however, then it is finally able to reap the rewards of a near-captive user base.

There are some caveats, however, when it comes to the power of classified advertising networks. Multi-homing (where participants list on or use multiple platforms) can undercut exclusive network advantages. Leading operators often respond to this challenge by integrating additional functionality or raising switching costs (often through loyalty programs, embedded payment systems, or robust user-verification measures). These make it more convenient and safer to transact on a single platform. Nevertheless, competition among fragmented platform markets can be fierce.

Trust and safety also play a pivotal role. Marketplaces, in particular online ones, often struggle with the issue of ‘information asymmetry’. In other words, sellers know more about the product or service they are selling than buyers, and so buyers can sometimes end up buying inferior products.

To combat this problem, platforms frequently offer warranties, money-back guarantees and dispute-resolution mechanisms, as well as putting significant effort into fraud prevention. Without these safeguards, users can be scared off by crowded listings, spam, and/or scams.

Maintaining ‘quality at scale’ requires ongoing improvements in content vetting, adherence to regulatory standards, and an ability to exceed user expectations. While network effects can be potent, complacency remains a pitfall – insufficient efforts to build and sustain user trust can open the door for competitors to launch a challenge.

The Evolution of Online Classified Ads: from Bulletin Boards to Integrated Vertical Platforms

In the early days of the web, online classifieds were simple digital bulletin boards with text-based ads, minimal imagery, and few safeguards. Over time, platforms began to incorporate features such as search filters, user verification, and photo/video galleries, all of which reduced friction and boosted engagement.

In the recruitment vertical, for example, some platforms now offer integrated human resources (‘HR’) management software and analytics, enabling employers to handle everything from job postings to onboarding – all on a single platform.

Platforms also now regularly incorporate social features, user ratings and specialised filters. Some even add payment and delivery options that reduce friction and bolster trust. Facebook Marketplace, for example, makes use of existing user identities to reassure buyers and sellers.

Other niche platforms devoted to specialist areas, such as classic cars4 or other categories of collectibles, cultivate tight-knit communities of enthusiasts. These fans value granular product details and differentiated ways to monetise their interest (e.g. in the form of auctions), and revel in the depth and transparency that only a specialised platform can bring.

While many established sites evolved gradually from basic listing services, some players jumped in at a later stage but still managed to become market leaders quickly, as they were able to leverage the existing digital ecosystems of their parent companies.

Alibaba’s Xianyu (闲鱼, ‘Idle Fish’)5 in China is a prime example of this phenomenon. This platform drew on its parent company’s massive e-commerce user base which already enjoyed established user trust (i.e., Taobao 淘宝). It also offered a transaction model which was initially fee-free for users,6 as well as a proven payment network (Alipay 支付宝).

These advantages enabled Xianyu to outstrip incumbents such as 58.com’s Zhuanzhuan (转转)7 and become China’s dominant used-goods marketplace.8 As of early 2024, Xianyu enjoyed >70% market share (calculated by gross merchandise value), with ~7x the monthly active users of Zhuanzhuan.

In Australia, REA Group (majority-owned by News Corp) established itself from the early 2000s as the go-to portal for real estate listings. Its flagship site realestate.com.au now attracts ~11mn monthly unique visitors. This represents user numbers which are ~70% higher than its closest competitor, Domain.

REA Group’s dominance is partly thanks to News Corp’s extensive media reach, as the parent funnels internet traffic and listings to REA. Although Domain has carved out a niche existence due to its expertise in certain metropolitan areas, REA Group’s scale and brand recognition enable the platform to command premium pricing with minimal resistance.

Establishing a clear ‘pole position’ in a specific vertical often produces outsized rewards. When a single platform captures the majority of user traffic – whether in second-hand goods, jobs, automotive, or real estate – then this company can typically set higher prices and operate with much fatter margins than its nearest competitors.9

As discussed earlier in this Insight, for a challenger to build a critical mass of users on both sides of the ‘marketplace’, this typically requires that the newcomer offers significantly better functionality or deeper specialisation than the leader already provides. Without such differentiation, even well-funded challengers may find that their users habitually revert to the incumbent, where ‘transaction friction’ is lowest and convenience highest.

In Part 2 of this two-part Insight, we take a closer look at recruitment platforms, and see how a Taiwanese company managed to build on its job listings business to create a comprehensive, HR-tech ecosystem.

Thank you for reading.

Romain Rigby, Andrew Limond

Buffett was still intent on acquiring newspapers as late as 2012, although by 2019 he had changed his mind, saying the newspaper business: “…went from monopoly to franchise to competitive to … toast”.

For instance, Schibsted, a Norwegian media group, published several major newspapers (including Aftenposten and VG) before venturing into digital classifieds in the late 1990s. The company later spun off those operations into Adevinta. Axel Springer (originally a German media group) leveraged its print heritage to build various leading online marketplaces, and recently announced plans to carve out and sell majority stakes in its two major online classifieds platforms to private equity investors.

OLX, founded in 2006 in Argentina, initially sought to position itself as the international version of Craigslist (the pioneering US-based online classifieds site launched in 1995), and quickly expanded into Spanish-speaking Latin America under the ‘Mundoanuncio’ brand. Today, OLX is majority-owned by Prosus (part of the Naspers group), and operates in more than 30 countries.

Hemmings, founded in the US in 1954 as Hemmings Motor News, began as a monthly publication featuring listings and market insights for vintage automobile enthusiasts. Today, it provides an extensive online classifieds marketplace, auction listings, and editorial content focused exclusively on collectible cars, thereby cultivating a dedicated community of buyers, sellers, and restorers.

Alibaba’s second-hand platform, named 闲鱼 (xiányú), literally ‘idle fish’, is also a homophone for 闲余 (xiányú) or ‘spare time/items’, reflecting its focus on repurposing unwanted goods.

In late 2024, Xianyu ended its ten-year ‘fee-free’ era by rolling out a platform-wide commission of 0.6% on all sales (capped at CNY 60 per order).

Zhuanzhuan was created by merging 58.com and Ganji.com, thereby consolidating the significant market share of its two predecessor companies in second-hand goods listings. This merger of the erstwhile market leaders came partly in response to the rapid rise of Alibaba’s Xianyu. Despite Zhuanzhuan forming close links with investor Tencent’s payment platform (WeChat Pay 微信支付) and social media functionality (WeChat Moments 朋友圈), this has not been enough to beat Xianyu.

In 2023, Xianyu introduced social features which encourage users to share interests and experiences. This helped Xianyu build its community to more than 500mn registered users, with a strong slant towards a younger demographic.

At a recent conference, Malcolm Myers, formerly Head of M&A at Naspers, explained that in any given classifieds market or vertical, once the leading player’s traffic share reaches at least 3x that of the second-ranked competitor, it usually gains significant pricing power and greater monetisation potential.