This Insight is not investment advice and should not be construed as such. Past performance is not predictive of future results. Fund(s) managed by Seraya Investment may be long or short securities mentioned in this Insight. Any resemblance of people or companies mentioned in this Insight to real entities is purely coincidental. Our full Disclaimer can be found here.

This Insight is an extract adapted from the Panah Fund letter to investors for Q1 2025.1

After several decades of relative global peace and stability, we are now confronting the third major geopolitical shock of the 2020s.

The first was the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. The second was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Following the inauguration of Donald J. Trump as the 47th President of the United States, we now face an international trade war launched by the US.

In the most recent Seraya webcast in November 2024 (transcript here), we accurately forecast the likely path of tariff policy under incoming President Trump, as well as the market reaction to these events. In reality, Trump’s policies – and the manner in which he has pursued them – have been even more extreme than we anticipated.

In this Insight, we review the events of ‘Liberation Day’ and its aftermath, ask what President Trump’s goals might be, and review the difficulties with his approach. We also review the ongoing trade negotiations between the US and its trade partners, and explain why we think China is not in a hurry to make a ‘deal’. Finally, we summarise our economic and market outlook in light of recent events.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

‘Liquidation Day’

“The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book V

“My fellow Americans, this is Liberation Day… 2 April 2025 will forever be remembered as the day American industry was reborn, the day America’s destiny was reclaimed, and the day that we began to make America wealthy again… For decades, our country has been looted, pillaged, and plundered by nations near and far, both friend and foe alike… American steelworkers, auto workers, farmers, and skilled craftsmen… really suffered gravely. They watched in anguish as foreign leaders have stolen our jobs, foreign cheaters have ransacked our factories, and foreign scavengers have torn apart our once beautiful American dream.”

Donald Trump, ‘Liberation Day’ speech, 2 April 2025

Rumour has it that President Trump was originally planning to hold his much-awaited ‘Liberation Day’ event on 1 April. Subsequently, however, he decided to shift the event to the following day, as he didn’t want anyone to think that his policy announcement was an ‘April Fool’ prank.

When President Trump stood up to speak at 4pm EDT on 2 April, it soon became clear why observers might have thought it was a joke. Trump announced sweeping tariffs (Figure 1), including a 10% baseline tariff on almost all countries around the world, and unexpectedly high ‘reciprocal’ rates on most trading partners – including US allies.

These tariffs represented the highest level of global trade barriers since 1909, higher even than the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariffs of the 1930s.

Trump claimed that these IEEPA tariffs were justified as the US had been “looted, pillaged and plundered” by trade partners, via unfair trade practices such as IP theft, value-added taxes, currency manipulation, unfair rules and lax pollution standards.

Trade advisor Peter Navarro reportedly pushed for hardline tariffs for their own sake, while Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent framed the Liberation Day tariffs as a “maximalist negotiating position”. In the end, President Trump reportedly made the final decision on ‘reciprocal tariffs’ just hours before the ‘Liberation Day’ announcement, without substantive planning or feedback from his advisors. (Subsequent remonstrations from supporters and financial backers such as Elon Musk appear to have been largely disregarded.)

Most economists criticised the ‘reciprocal’ tariff formula as simplistic and arbitrary, and not reciprocal at all, given that the proposed tariff rates are based solely on 2024 bilateral goods deficits. The tariffs ignored trade in services and disregarded the concept of comparative advantage (Figure 2), thereby making the assumption that any country enjoying a bilateral trade surplus must be ‘cheating’.

Many economists have likened the tariffs to a supply shock such as an oil price spike, or a large regressive tax increase, immediately predicting an adverse economic outcome.

Playing With Fire & the Art of Capitulation

"Well, I thought that people were jumping a little bit out of line. They were getting yippy, you know? They were getting a little bit yippy, a little bit afraid.”

Donald Trump comments on bond market dysfunction and his reasons for pausing reciprocal tariffs, 9 April 2025

Although the markets had been expecting higher Trump tariffs, the ‘Liberation Day’ announcements were far more extreme than most people’s ‘worst case scenario’. Investors quickly judged that President Trump had unilaterally declared a global trade war. US allies were particularly shocked that they had been targeted.

The market reaction was swift and brutal – the ‘Trump Dump’ – as investors liberally liquidated their risk positions in the wake of ‘Liberation Day’.

Equities around the world plunged amid fear of stagflation and extreme uncertainty. In the two days following the 2 April tariff announcement, the S&P500 index declined by as much as -10.5%, with S&P futures then falling by a further -5.5% on the morning of Monday 7 April, after Trump spent the weekend playing golf (Figure 3) and White House aides promised that Trump would not back down on tariffs.

International equity markets also saw waterfall declines. The Nikkei 225 fell -13.8% from the close on Wednesday 2 April to the intraday low on the following Monday, with the Eurostoxx declining as much as -14.4% over the same period. The Hang Seng Index sold off -16.9% from the 2 April close to its lows on 9 April. Credit spreads – the classic path of contagion from financial markets to the real economy – also started to blow out.

In the week after ‘Liberation Day’, normal market correlations then broke down, as equities continued to suffer while US bonds and the US Dollar sold off hard.

Investors guessed that the reason for the Treasury market instability was probably a blow-up of the basis trade, or a forced unwind of bets on bank deregulation. Others surmised that foreign investors (perhaps China) had started to dump US Treasuries. Or perhaps it was a fear of tariffs stoking inflation that had caused the spike in bond yields.

The uncomfortable backdrop to the Treasury market turmoil is of course the US fiscal situation. The US must refinance more than one-quarter of its US ~$36tn in debt obligations this year. If Trump really is successful in shrinking the US current account deficit, then foreign trade partners will have less money to recycle into US debt markets. They are probably also less inclined to buy US assets, given the erratic nature of White House policymaking.

On 9 April, even as Treasury Secretary Bessent tried to reassure markets, the turmoil was severe enough that President Trump was persuaded to back down and pause reciprocal tariffs for 90 days – just hours after they went into effect. (Pressure to back down on the reciprocal tariffs from certain Republican donors and prominent Trump supporters might have also played a role in this policy reversal.)

The only exception to the tariff pause was China, which had already retaliated by implementing its own tariffs on the US. Over a few days, there followed a tit-for-tat escalation on tariffs between the US and China, which by 9 April had taken US tariffs on China to 145% on most products, and Chinese tariffs on US goods to 125% by 11 April.

Less than a day after announcing these ‘maximum’ tariff levels on China, President Trump ‘blinked’ and implemented an exception for electronics, including computers and smartphones. (Separate tariffs on electronics, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals and critical minerals are still in the pipeline, however, and will likely be implemented following Section 232 investigations.)

What’s the Plan, DJT?

"I believe very strongly in tariffs... America is being ripped off... We're a debtor nation, and we have to tax, we have to tariff, we have to protect this country."

Donald Trump interview with Diane Sawyer, August 1989

"Our politicians have aggressively pursued a policy of globalisation, moving our jobs, our wealth and our factories to Mexico and overseas. Globalisation has made the financial elite... very, very wealthy... But it has left millions of our workers with nothing but poverty and heartache... Skilled craftsmen and tradespeople and factory workers have seen the jobs they love shipped thousands and thousands of miles away... This wave of globalisation has wiped out totally, totally, our middle class. It does not have to be this way. We can turn it around and we can turn it around fast."

Donald Trump, speech on trade in Pennsylvania, 28 June 2016

Taking a step back, it is important to consider why President Trump has implemented tariffs, what his goals are, and what might be the difficulties with his approach.

It is well-known that Trump has been a big believer in tariffs since the 1980s. The US President appears to be trying to use tariffs in the following ways:

As a tax, to raise revenues for the government (which means the 10% base tariff rate and probably also sector-specific tariffs such as aluminium, steel and autos are non-negotiable, as they may be used to fund other tax cuts);

To raise the price of imports and encourage the onshoring of manufacturing; and,

As negotiating leverage to compel trading partners to comply with his demands.

Trump is pursuing a tariff strategy because of a belief that globalisation destroyed US manufacturing jobs and devastated the US working class. One of his core goals is to reindustrialise the US economy and bring back manufacturing jobs. Understandably, the White House also has national security concerns, as the US is dependent on foreign nations (especially China) for critical goods such as medicine and semiconductors.

Tariffs align with the new ‘America First’ view that since World War II, the US has carried an unfair financial, social and military burden by underpinning the international geopolitical and economic system. This has allowed other nations to benefit at America's expense by ‘free-riding’, especially on trade and defence. Trump’s probable endgame thus involves rebalancing the global system to be ‘fairer’ to the US.

Trump’s analysis does seem to have flaws, and, his grasp of trade economics seems tenuous. (For instance, he regularly conflates the idea of trade deficits with ‘losses’ on a corporate income statement.)

His worldview also overlooks the immense economic and geopolitical benefits the US derives from its global leadership role. These include: the US Dollar’s ‘exorbitant privilege’ as the global reserve currency (which reduces the cost of borrowing for the US government, companies and citizens alike); the ability for the US to magnify its geopolitical heft through global alliances; as well as allowing US consumers to benefit from a vast array of cheap, high-quality imported goods.

Retreating from this leadership role risks sacrificing these substantial advantages for the US and instead boosting rivals – but President Trump and his supporters will probably only miss these benefits once they are gone.

It is also valid to ask whether President Trump is trying to tackle only the symptoms of US problems, or the underlying issues themselves. For instance, the most pressing issue facing the US right now is probably fiscal sustainability. Ironically, Trump’s actions since his inauguration might bring forward the date of any fiscal reckoning. Another US (and OECD) problem has been the erosion of STEM education capabilities in recent decades.

Moreover, complaining about a ‘raw deal’ seems inconsistent with ~15 years of US economic and market outperformance relative to other developed nations. The world has been a strong believer in ‘US exceptionalism’, but Trump’s tariffs put this at risk.

The ‘America First’ riposte to these observations would be that the working class has not benefitted from ‘US exceptionalism’. More importantly, there are those in the White House who would add that current US supremacy is based on shaky foundations (especially fiscal overreach). The US runs large double deficits and has a large negative international investment position. It is also dependent on other nations for key imports which are vital for national security. It is thus best to act now, before it is too late.

Some believe that President Trump is attempting to pursue a ‘masterplan’ that allows the US to preserve the substantial benefits that it receives from the post-WWII international order (including US Dollar reserve status), while at the same time mitigating the social and national security costs of these policies for the US.

The most well-known proponent of such a plan is Stephen Miran, who in November 2024 published ‘A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System’. This argued that economic imbalances are largely due to the US Dollar’s persistent overvaluation, which is in turn derived from the greenback’s global reserve status.

Alongside tariffs, Miran also suggests using currency policy (including multilateral agreements such as a potential ‘Mar-a-Lago Accord’), US unilateral actions (e.g., fees on foreign Treasury holdings or reserve accumulation), and even forced bilateral deals (perhaps to ‘term out’ the duration of US debt). He has also advocated ‘burden sharing’ by allies, including buying more US goods (including defence exports), investing more in the US, or even foreign governments making direct payments to the US Treasury.

Miran warns, however, that the plan risks significant financial market disruption, and that a successful outcome will require gradualism and/or coordination with allies.

“There is a path by which the Trump Administration can reconfigure the global trading and financial systems to America’s benefit, but it is narrow, and will require careful planning, precise execution, and attention to steps to minimise adverse consequences.”

Stephen Miran, ‘A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System’, Nov 2024

Critics point out that President Trump's actions since inauguration have been neither careful nor gradual. Instead, his unilateral decisions risk undermining the institutions and alienating the allies who are necessary to ensure a positive outcome.

Assuming that the reshoring of manufacturing to the US is one of President’s Trump’s most important goals, the question is whether this would have been best accomplished by working together with allies – using a combination of carrots and sticks – or by simply attempting to beat them into submission?

Imagine if President Trump had on 2 April and announced a more nuanced industrial policy, which involves working with allies to impose targeted tariffs on the countries and sectors where trade abuses are most ‘rampant’, but also giving tax breaks and other incentives to invest in America? The process of onshoring more advanced manufacturing in the US had already been started by President Biden’s CHIPS & Science Act (e.g. for semiconductors).

It’s important to note that tariffs alone cannot build US factories. CEOs must believe that policy will remain stable for years before they are willing commit to capex, especially when it comes to strategic and expensive projects such as factories. Otherwise, how can they be sure these projects will have a positive payback?

President Trump, however, has chosen to take a more adversarial, ‘Art of the Deal’-style approach. His strategy appears to be improvised rather than based on careful planning. The outcome will depend on his personal ability to make a correct assessment of the US’s leverage, and his ability to reach favourable outcomes in negotiations.

How to Lose Friends & Alienate People

"I am telling you, these countries are calling us up, kissing my ass. They are dying to make a deal. 'Please, please sir, make a deal. I'll do anything sir.'"

Donald Trump comments on US trade partners at the National Republican Congressional Committee Dinner in Washington, 9 April 2025

“What the US is saying is unreasonable, the theory is a mess, and there is no consistency. If Japan were to negotiate on the basis of what [the US] is saying, it [would be like negotiating with] a juvenile delinquent who is attempting extortion. If you put money in the hands of an extortionist, he’ll just come back and ask for more… You shouldn’t make concessions to someone who is not straight up.”

Shinji Oguma (member of the Japanese House of Representatives for the Constitutional Democratic Party) floor speech in the House, 17 April 2025

Following President Trump’s decision to pause implementation of his ‘Liberation Day’ reciprocal tariffs by 90 days (these will not go into effect until 9 July), the US is currently engaged in trade negotiations with ~90 countries. US tariffs on China, however, have been increased to 145%.

The US has given Japan priority in these negotiations, given its historical status as a key US ally. Talks commenced in mid-April and are continuing. Discussions with Korea, India, and Vietnam have reportedly also started, and are expected to continue into June.

Treasury Secretary Bessent recently stated that: “I think...at the end of the day that we can probably reach a deal with our allies… And then we can approach China as a group.” This – together with the pause in ‘reciprocal’ tariffs on all countries but China – indicated a shift in strategy away from the original ‘Liberation Day’ across-the-board tariffs and global trade war, towards a more focused ‘attack’ on China.

President Trump believes that the White House is able to bring to bear substantial pressure against its trading partners – including its allies – to achieve quickly its desired outcome in negotiations. Such leverage involves tariffs and access to the US market, and maybe also access to US military protection (in the case of security allies such as Japan).

It is still unclear exactly what concessions the White House is seeking from each of its trading partners. In the case of Japan, it seems likely that the US wants to see laxer safety standards on automobiles, lower agricultural import barriers, and investment in US LNG projects. For other trade partners such as Vietnam and Mexico, there will likely be robust discussions on how to crack down on rerouting of exports from China.

There have reportedly not yet been any discussions about pushing Japan to let the Yen appreciate against the US Dollar, on ‘terming out’ US Treasuries held by Japan, or on military matters (e.g., Japan paying more to host US military bases), although these topics will probably be broached later.

Senior politicians in Japan have been critical of the US approach, noting that the US stance is changing frequently, and that the White House has promulgated numerous incorrect facts about the trade relationship between the two countries.

In Japan, there is an Upper House election planned for July 2025. The current ruling party’s hold on power is tenuous – for Prime Minister Ishiba, it would be dangerous to concede too many points to the US in negotiations. Indeed, the leader of every country with which the US will conduct trade negotiations in coming weeks and months have domestic constituencies they must consider; they cannot just capitulate to US demands.

Many US trade partners – including Japan – have seen the way that President Trump has treated his neighbours in North America. They are thus, unsurprisingly, wary of coming to any deal with the US, as they fear that President Trump might change his mind and seek to renegotiate whenever it suits him. In other words, trust has been eroded – most foreign leaders simply do not see President Trump as a reliable interlocutor.

When it comes to the European Union (‘EU’), it would seem particularly difficult to reach a meaningful trade deal with the US in the near term. Although the US is the EU’s largest trading partner, intra-EU trade is more than four times larger than the EU’s trade with the US. Moreover, the EU is also a large importer of services from the US – which gives the EU the ability to retaliate (e.g., by increasing taxes on US tech companies), should they decide to do so. Given that the EU is made up of 27 countries with different priorities, internal disagreements also seem likely. Moreover, following the ‘US ‘betrayal’ on NATO and recent pressure on Ukraine, there is currently a distinct lack of transatlantic trust.

It usually takes years to negotiate a trade treaty between two countries. It beggars belief to imagine an understaffed US Trade Representative’s Office will have sufficient bandwidth to negotiate complex trade treaties (which may also involve currency and national security issues) with ~90 countries in less than three months.

Indeed, given the difficulty in successfully negotiating any proper trade deals in such a short timeframe, it seems likely that the White House will push its trade partners to make some quick and superficial trade concessions. That way, Trump would be able to declare ‘victory’ quickly. If that is the case, however, then that would probably mean that the White House will be back later this year or in 2026 to ask for more meaningful concessions from its partners. (This would be similar to the way that Canada and Mexico have been under ongoing pressure from President Trump for some time.)

Others have suggested after asking for some cosmetic trade concessions from trade partners in the coming weeks, the White House will then demand that they all work together to isolate China. (If so, this also suggests that ‘China hawks’ within the Trump administration might have more influence than the media believes.)

If so, this would lead to different challenges. For instance, if – as part of the current trade talks – the US were to demand that its trading partners should place tariffs on China, thereby forming a trading bloc with the US, this would place Japan and other Asian countries in an almost impossible position.

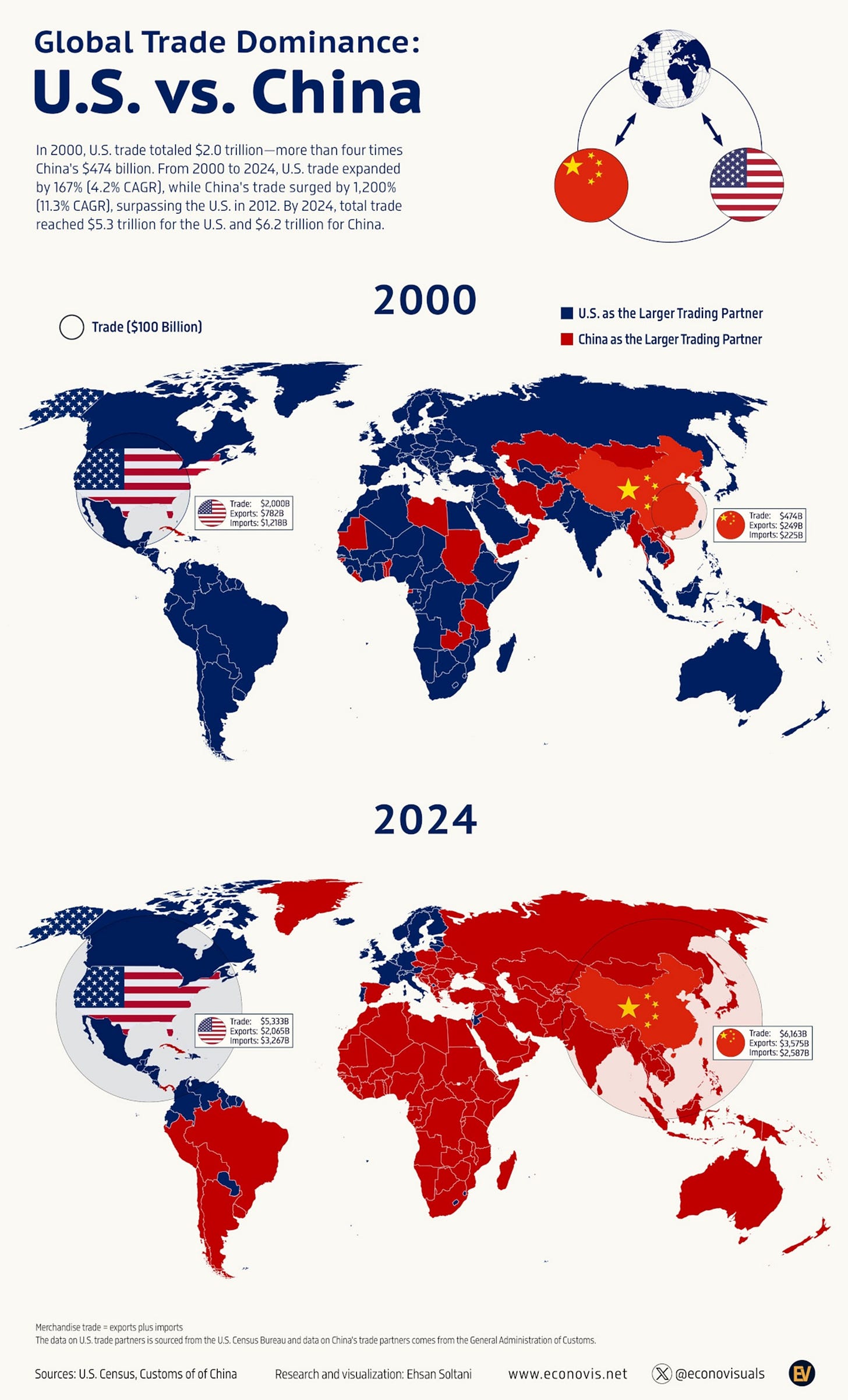

China was Japan’s largest trading partner in 2024, with the US in second place (although of course Japan’s #1 export destination was the US, and China was Japan’s largest source of imports). The same pattern is true for most other Asian nations, including Taiwan, Korea, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand – China is now their largest trading partner (Figure 6).

From ‘Chimerica’ to MAGA Chimera

“The seven deadly sins… Stop stealing our intellectual property, stop forcing technology transfers, stop hacking our computers and stealing our trade secrets, stop dumping into our markets and putting our companies out of business, stop… state-owned enterprises from heavy subsidies, stop the fentanyl, stop the currency manipulation.”

Peter Navarro criticises China on a Fox News interview, 4 August 2019

“I think there are probably no two economies that are more interdependent than the United States and China, even now, and it is also true that no two countries in the world are more uncomfortable with that interdependence.”

Kurt Campbell speaks on the Foreign Affairs interview podcast, 17 April 2025

Ever since China joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001, the mutual interdependence between the US and China – ‘Chimerica’ – has grown to colossal proportions. The US has grown dependent on Chinese goods, and China has recycled its enormous current account surplus into US Treasury securities, (and more recently into USD-denominated ‘One Belt One Road’ loans, i.e. offshore US Dollar assets).

As we discussed in a December 2020 investor webcast,2 we believe that it was the change in global monetary system in 1971 to a ‘fiat money’3 mercantilist Eurodollar standard which has enabled the US to run such large and growing double deficits over the last 50 years. This dynamic also set the scene for the rise of the ‘export tigers’ in Asia (i.e., Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, and more recently Vietnam).

As laid out in the same webcast, our view has been that by 2020, the post-1971 monetary system was already being pushed towards its breaking point by factors such as: the gradual diversification of central bank reserves (i.e., away from the US Dollar); national security concerns (i.e., an increasing inability for the US to produce vital defence and medical goods – as seen during the pandemic); and by growing social pressures (e.g., inequality and ‘deaths of despair’). This has led to MAGA-style protectionist populism in the US political sphere.

With the re-election of Donald J. Trump as 47th President of the US – someone who has long railed against these issues – the scene was set for a reversal. This is now underway. The country which enjoys the largest trade surplus with the US is China, which is hostile to US interests and has managed to gain a technological edge in various areas. This is why Beijing is firmly in the tariff crosshairs.

Although many commentators assume that >145% US tariffs on China will effectively halt trade between the two countries, this is not necessarily the case. In the near-term (while the rest of the world is only subject to ~10% tariffs), some goods will likely be rerouted through other countries. Even with massive tariffs, however, US importers will find they have no ability to source from other countries, given China’s control of various manufacturing verticals. In that case, US prices will rise, and purchase volumes will fall.

China, sensing danger, has adopted a ‘charm vs harm’ strategy. President Xi has attempted to beef up his multilateral trade credentials. He has also reached out to numerous other countries in attempt to counter US threats.

There have already been trilateral talks between China, Japan and Korea. President Xi Jinping visited Vietnam, Malaysia and Cambodia in mid-April, pledging cooperation and signing dozens of trade deals. Premier Li Qiang also spoke with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen on 8 April, and an EU-China summit is due to be held in July in Beijing. On the other hand, President Xi has also warned other nations against reaching deals with the US that might damage Chinese interests.

President Xi has also urged other countries to join China in resisting ‘unilateral bullying’, although there have so far been few takers. Most countries would rather maintain the status quo and remain on speaking terms with both the US and China.

US tariffs are not an attractive option, but neither is the prospect of becoming a captive market for a deluge of Chinese exports. These other countries (just like the US) will likely remind China that it should boost its own domestic consumption and not dump excess exports in their markets.

There are also geopolitical reasons for other nations to be wary of China. Europe will be cautious given China’s key role in supporting Russia’s war on Ukraine. Asian nations will be vigilant given China’s designs on Taiwan and its manoeuvres in the South China Sea.

In recent years, China has faced a serious slowdown as a result of a bust in its real estate market amid rapidly deteriorating demographics. At the same time, the country has made impressive technological progress in numerous areas, which has helped to drive the country’s powerful export engine. These crosscurrents coexist within an increasingly autocratic system, which can make it challenging to work out exactly which factors are most dominant in China at any given moment.

There are some in the White House who believe that China is so dependent on exports to the US that President Xi will be forced to negotiate when threatened with high tariffs. In their view, the alternative is massive economic pain and maybe even a financial crisis in China. (It’s worth noting that the Trump administration’s China expertise has been eroded by the recent Laura Loomer purges of the National Security Council.)

As China’s cool, tit-for-tat reaction to US tariffs and targeted retaliation has made clear, President Xi does not share the White House’s belief in Chinese weakness. Recent commentary from senior White House officials has also been sufficiently incendiary that it would not be politically acceptable for him to cave in to US pressure.

Moreover, the belligerent nature of US tariffs also presents President Xi with a valuable opportunity to lay the blame for any coming economic hardship in China squarely on President Trump. This new narrative is a welcome change from the miasma of discontent which had prevailed in China in recent years, following self-inflicted setbacks such as Covid lockdowns, as well as crackdowns on the real estate sector and private enterprise (e.g., tech and education companies). Now the Chinese populace seems ready to rally behind President Xi against an external aggressor.

In any case, President Xi believes that China is much more capable of withstanding pain than the US. After all, the US is just a ‘paper tiger’. In contrast, just look how much pain that the Chinese population were willing to suffer during ‘Zero Covid’. Political and social control in China remain strong.

In contrast, President Trump has already ‘blinked’ several times this month when placed under pressure. For example, when faced with turmoil in the bond markets, Trump suspended implementation of reciprocal tariffs. After upping tariffs on China to the highest level, he then suddenly made a quiet exception for electronics (likely at the behest of Apple and other US companies). He then backed down on threats to fire Federal Reserve (‘Fed’) chairman Jerome Powell after warnings from advisors and a bad reaction from US Treasuries and the Dollar. The US is negotiating against itself.

We believe that President Xi is trying to follow Napoleon’s advice: “Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake”. China assesses that within a few months, US price levels will be much higher and growth will be slowing. That will likely place Trump under increasing pressure from voters, and by extension from Republican politicians, who will be starting to worry about the mid-term elections next year. In other words, President Xi likely believes that time is on his side, and that China has escalation dominance.

The White House appears to be trying to de-escalate tensions with China and seek a offramp via negotiations. While China would likely welcome tariff relief, President Xi is not responding.

Trade talks, when they happen, will likely first take place at junior levels. Early direct discussions between Presidents Xi and Trump seem unlikely given that Chinese side sees Trump as an unreliable and erratic interlocutor. (Perhaps the clearest sign of impending negotiations would be a Beijing visit by special envoy Steve Witkoff, apparently the only person whom Trump trusts to carry out his foreign policy agenda.)

Some believe that China will have to implement a much larger consumer stimulus in 2025, to offset tariffs from the US and support the domestic economy. While this might happen, we would caution that President Xi is not a natural supporter of ‘consumerism’.

Indeed, President Xi has a choice to make in 2025. Will he decide to stand firm against President Trump, and choose to adopt a much larger consumer stimulus to support the economy? Or will he decide to follow a darker path, involving less domestic stimulus amid mounting military purges, and a greater emphasis on nationalism to bolster the nation (which would no doubt involve more pressure on Taiwan). Xi’s decision will depend in part on the extent to which the US now attempts to isolate China.

Market Outlook & Portfolio Implications

Historic US tariffs will feed into higher price levels in the coming weeks and months, squeezing consumers and causing a hit to growth in the US. In other words, stagflation is on the horizon.

The erratic, stop-start nature of White House policy announcements – on tariffs and other matters – means maximum policy uncertainty (Figure 10). Faced with an uncertain future reality, companies around the world are already starting to freeze investment and hiring decisions.

The US is likely to slip into recession, dragging other developed nations with it. That said, the US might be in recession already (Figure 11). The US and China are now locked in a trade war of attrition, and we do not anticipate imminent relief. Expect a torrid summer.

Despite the poor growth outlook, the Fed under chairman Powell will likely not rush to cut interest rates. This is because US tariff policy is erratic, and there is a serious risk of inflation in certain scenarios. Central banks elsewhere in the world, however, are already moving to cut rates, with only a few exceptions (e.g., in Japan where the labour market remains tight).

We believe that only those countries with enough ‘fiscal space’ to carry out significant stimulus will be spared from a significant economic slowdown. In Europe, probably the only country of any size which has the ability – and now the willingness – to stimulate its economy is Germany.

President Xi will have to make a political decision whether he wishes for China to stimulate domestic consumption. Elsewhere in Asia, various other countries – including Taiwan and Vietnam – have plenty of room to boost their domestic economies. This year, under a new leader, Vietnam is embarking on an aggressive program of reform and infrastructure buildout. Given the high degree of trade exposure for Vietnam and certain other Asian economies, however, the net effects of the global trade war will likely not be positive.

The one country where fiscal space is now definitively lacking is the US. The country’s fiscal deficit is now approaching 7.5% of GDP. Hopes of US ~$1tn in spending cuts by Musk’s DOGE have been abandoned in favour of a more modest target of $150bn. If Congress manages to pass tax cuts later this year, and if the economy deteriorates as we expect, there is of course a risk of an even larger fiscal deficit. It is interesting to note that US credit default swaps have blown out to 59bps – a similar level to Italy and Greece.

The US also faces a record funding refinancing requirement for Treasuries in 2025 – a total of US ~$9.2tn (a quarter of the total US debt pile, and equivalent to >30% of GDP). President Trump is attempting to eviscerate the US trade deficit (i.e., other countries’ surpluses), and has also made it clear that US allies are expected to foot their own bill for national security. All of this means that these nations will have less money to spend on US debt securities.

Foreign investors own an estimated US ~$7.2tn in US Treasury securities. Given that the White House has also declared a global trade war, most countries (especially China) will presumably be less willing to fund America’s spendthrift ways. President Trump’s disruptive threats to Fed chairman Jerome Powell have also undermined confidence that the central bank can remain ‘independent’. So far, the courts and Congress have done little to restrain Trump.

These factors suggest that all else being equal, the path of least resistance for US Treasury yields will be higher – unless there is a collapse in economic growth.

President Trump has recently taken action to freeze federal funds for Harvard and other universities. The likely impact of this conflict is that various colleges will soon need to draw down on their endowments to fund budgets. Yale is reported to be considering secondary sales of US ~$6bn in private equity stakes. Such action from major endowments compounds the woes faced by the private equity industry, and also seems likely to pressure asset prices.

Foreign investors also own an estimated US ~$19tn in US equities (~20% of total US market capitalisation) and $4.6tn in corporate credit (~30% of the market). The willingness of foreign investors to buy an increasing volume of US securities has underpinned the concept of ‘US exceptionalism’ in recent years. We expect to see these foreign flows go into reverse. This will probably catalyse a ‘normalisation’ of overextended US equity valuations, which will come on top of weaker earnings.

The US Dollar has moved sharply lower since early April as international investors have lost confidence in US policy and fiscal rectitude. We expect this trend to continue. Unsurprisingly, the ultimate beneficiary of all these developments has been gold – the ultimate haven asset, which recently hit a record of US $3,500/oz.

While the price of gold bullion is now overbought and so vulnerable to any ‘positive’ news flow, it is still ‘under-owned’ by investors. Gold stocks have also lagged the yellow metal. We thus think it makes sense to add to positions in both bullion and gold stocks on any pullback.

In the latest Seraya webcast (November 2024), we warned of the possibility of a US fiscal crisis in 2025. This is now a real risk, and will depend on the path of US policy. It’s sobering to think that we may now be witnessing the ‘beginning of the end’ of US hegemony.

Elsewhere in the world of geopolitics, we note that President Trump has not yet made the progress he had hoped on ending the war in Ukraine. While talks with Iran currently seem to be progressing more smoothly than expected, any deterioration in negotiations might lead to US-Israeli strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities. This would likely cause a serious deterioration in the Middle East security situation, and a spike in the oil price.

We reiterate our view (which we have held since late last year) that in the current environment, it is not desirable to have large exposures to small trade-exposed economies, or to companies which are dependent on exporting goods. In Asia, we retain a bias for firms which are more exposed to ‘domestic demand’, in countries which have the ability to support growth through fiscal stimulus.

As we confront such momentous events – “the likes of which we have not seen for 100 years” – we wish you the serenity to accept the things that cannot be changed, the courage to change the things that can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

Thank you for reading.

Andrew Limond

The original source material has been edited for spelling, punctuation, grammar and clarity. Photographs, illustrations, diagrams and references have been updated to ensure relevance. Copies of the original quarterly letter source material are available to investors on request.

Available to investors on request.